Adventure in Everyday Living:

Island Park Scout Camp

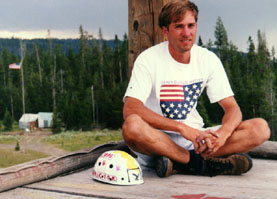

Shaun kicks back in his office. Nice view, eh? That's Yellowstone in the background.

|

The COPE Freedom

Award Thunder cracks and rolls over the valley as heavy, black clouds scrape mountain ridges to the West, then crawl slowly across the valley toward us. The lightening should reach us within twenty minutes, I estimate, together with drenching rain and high winds. If I'm right, we'll have to close the tower early, and we could actually make it to lunch on time for once. "Hey, Milton!" I yell to one of my COPE Staff on the ground forty feet below, "Don't put anybody else in harnesses till we see how fast this storm's coming, okay?" The five scouts waiting inside the tower and three waiting on top might be all we can safely handle for today. "Okay!" Milton yells up. The last half of the word is lost in another sharp crack of thunder. "Seventy three, tower," my radio crackles. It's Paul at waterfront. "This is tower, go ahead seventy three," I answer. "You guys seen that action on the horizon?" "Yeah, we're keeping our eyes on it." Another bolt seems to reach the ground somewhere across the caldera and I begin counting the seconds before the thunder reaches us. "We're closing down waterfront, see ya at lunch. Seventy three out." "See you there. Tower out." Two scouts finish rappelling and I call for two more to come up the stairs and clip in to the safety lines. I look off to the West again. The storm is moving faster than I thought and we've learned not to underestimate the power of Nature at Island Park Scout Camp. On my helmet, I've painted three things: COPE Director in red; Justice, the nickname I've been given in camp; and a yellow lightning bolt in memory of the time the climbing tower was struck with me standing less than three feet away, a jolt of electricity jumping through my hands. The front edge of the clouds covers the sun and a cold wind hits the tower seconds later. It's always the same, and the real show will arrive in minutes. I've grown to love nature's treacherous displays of power. "How many more scouts do we have?" Jeff asks, looking a bit concerned. "Three in the hole," I answer, "we should be okay." "Good thing Jake was here last week, eh?" "Yeah. Good thing." None of us have forgotten Jake yet. I doubt we ever will. His name still comes up frequently among the COPE Staff. He has become something of a hero to us, and it happened in a way that none of us would have expected. Now I look over at Jeff's belay station and remember this same time last week.

The sun was shining then, and only a light breeze blew across the caldera--barely enough to keep the mosquitoes away. The tower had just closed for lunch and one rappelling line had been pulled up and untied. A few COPE Staff members and a scoutmaster stood in front of a scout tied to the other line, who stood outside the handrail on the edge of the tower and looked down. "Hey, Jake, these ropes would hold a cow, a school bus, and your bedroom. You're totally safe," Jeff said reassuringly. Jake's eyes showed two things: a fierce determination to go down the rope and tears that betrayed his fear of heights. "You don't have to go," Jon reminded him. That was COPE policy--you never force anyone to do anything they don't want to. Jake knew the policy well. He had already stood here for an hour today and another hour yesterday, trying to build up the courage to go down, to let his determination beat out his fear. After yesterday's hour, Jake had finally agreed to walk down the tower stairs and go to the bunny hill--where he could practice his technique six inches off the ground--with a promise to return and try again later. Now lunch time had come for the staff, but as long as Jake wasn't giving up, neither were we. Jeff spoke again. "Hey, Jake, why don't you try just sitting down until the rope holds you? You'll feel a lot more secure once you feel the rope catching you." Jake nodded his head once and lowered his body slowly the four inches it took for the slack to disappear. "Feel better?" asked Jeff. Jake nodded his head again, then stood up and gripped the handrail as tightly as before. "Maybe if I go down next to him," offered his scoutmaster. He had been here with him the entire time. "Good idea," I said, "we could even have him step down and stand on your leg. That would get him past the first scary step." Jon picked up the rope that had been tied to the other side of the tower and reattached it above Jake. We clipped the scoutmaster in and he lowered himself over the edge. "Okay, Jake, can you step down onto my leg?" he asked. Jake paused. "If you don't like it, you can go back up." Jake did his usual nod and stepped down slowly, carefully. "Way to go, Jake!" everyone shouted. "Good job!" "You're doing great!" "The hard part's all over now!" Jake smiled a bit through the tears that had filled his eyes again, then looked down. "Okay, Jake, you're doing great. Now can you lean back against the rope?" "You don't have to go," reminded Jon. This time he shook his head no and stepped back up onto the tower. "Do you want to come back and try it again later?" we asked. Jake nodded and stepped back inside the rail. We unclipped him from the ropes and sent him down the stairs with plenty of encouragement and congratulations for being brave enough to keep on trying. His scoutmaster rappelled to the ground and we started untying the knots. "We're gonna be late for lunch again," said Jon. "Who cares?" answered Jeremy. "Yeah," Jon agreed, "We're just doin' our jobs." The scoutmaster turned back and yelled up toward us as he walked back to his own campground, "Hey, thanks, you guys!" We smiled and waved back. "No problem! Come back when you're ready, Jake, there's no hurry."

That's the difference between last week and today, I think to myself. Today there is a hurry. The first raindrops hit the tower as we clip the last scouts in to the ropes and send them over the edge with hurried instructions and safety reminders. The wind has picked up to forty or fifty miles per hour by the time we untie all but one rope and Jeff looks at me questioningly. "Who's gonna walk down the stairs?" he asks hopefully. "Go ahead and take the elevator--I'll walk," I answer. Jeff smiles and thanks me, then hooks into the rope and disappears over the edge. Once he's on the ground, I untie the rope and coil it around one hand. I don't mind being the last one down. The tower has the best view in camp--I call it my office. And there's nowhere I'd rather be when the wind and rain have kicked up, creating the impression of standing on the deck of an old wooden ship in a heavy storm at sea. I walk to the edge and look out over the plains to the edge of thick pine forest that begins two miles away before creeping up the mountains, still snow-capped from last Winter. The wind hits me hard, knocking me back a step or two. I half expect a wave to crash over the side of the tower and sweep me away. Thunder cracks to the north less than a second after the lightning made me blink, and I decide to go down. I probably shouldn't try for a second close call, I think out loud. Once inside the tower, I glance up and read the boards where I hung on a rope to paint the scout law and our own COPE 7: Communication, Personal Responsibility, Safety, Teamwork, Leadership, Trust, and Self Esteem. Even though I had recently become an assistant varsity team coach, I had never heard of COPE until three weeks before I started working at IPSC. When I applied for the Director's job, I only knew that I would run the climbing and rappelling tower, the high-wire course, and a series of other challenging events. I knew that COPE stood for challenging outdoor personal experience, and that the last two words had been changed from physical encounter. Once I had been trained and certified at National Camping School in Washington and started work here, I understood why they were changed. COPE's challenges come in many different forms. For some, like Jake, the challenge is to overcome fear. For others, the challenge is to communicate effectively, to solve tricky problems, to lead a patrol well, or to build mutual trust and enhance self esteem. Guiding patrols through our Low COPE course and watching them progress is one of the most rewarding parts of our job.

The third day that Jake appeared, I was sitting alone in the COPE Shack, waiting for my Low COPE group while designing a poster of the COPE 7 to hang on the wall. Outside, Jeremy's group made their way over the twelve foot wall while BJ's group swung blindfolded and mute across the Nitro Pit--a thousand-foot-deep crocodile-and-piranha-filled gorge. Suddenly a scout ran inside the shack and told me I was supposed to hurry over to the tower. The scout was out of breath from running and his voice sounded urgent. I grabbed the radio from the table and ran outside, hoping I wouldn't find an emergency or accident waiting at the tower. What I found was Jake, hanging from the rope, half way down the tower. His eyes remained fixed on the wall before him as he lowered slowly, one step at a time, toward the ground. On top of the tower, the rest of the COPE Staff and Jake's scoutmaster shouted encouragement. "Good job, Jake! You're doing great! Way to go!" I crossed my arms and watched. As Jake finally neared the ground, he pushed against the tower with both feet and swung a few feet out. When he had landed and pulled the rest of the rope through his figure eight, I approached him. "I wanna be the first to shake your hand, Jake," I said, reaching toward him. He took the hand and smiled a little without looking up. I couldn't tell who was more excited--him or everyone else standing on the tower. I returned to take care of my Low COPE group, but that was not the last I would see of Jake and his scoutmaster. The scoutmaster approached us later that evening as we opened the tower again. "Thanks, guys, I really appreciate your patience," he said. "No problem," everyone answered. And we meant it. It was helping people like Jake that made our jobs worthwhile. "Jake's a completely different person," he told us. I wondered what that meant. I wondered how this had changed his life and what it would mean to him in the future. As Jeff and I closed the tower that night, I asked his opinion. "I don't know," Jeff answered. "I don't think he even knows yet. But we should find something to do about it." By the time the Friday evening campfire rolled around, we had decided what to do. After each patrol had done their skit--many of them jumping over the campfire bowl banister into the cold lake--it was staff's turn to hand out awards. Honor Camper awards were handed out to patrols who had kept their sites clean and the big fish contest winner was announced along with various others. When COPE's turn came, I stepped forward with Jeff, holding a piece of purple webbing tied in a loop with a water knot. The applause from the last award died out, and as silence returned, I began to speak. "I believe that the award I'm about to give out is the most prestigious award given in camp. You can't earn this award by keeping your campsite clean. You can't earn this award by tossing a worm in the river. You can't even earn this award with hard work. "We at COPE believe that 95% of the world's problems are caused by fear. Fear of differences causes racism and bigotry, fear of work causes laziness and crime, fear of reality can result in drug abuse and depression. If we aren't willing to stand up to our fears--whatever they may be--then we're in serious trouble. Only overcoming our fears can make us free. "With this in mind, we created the COPE Freedom Award. It carries one of the mottoes of our COPE Staff--Never Let Fear Stop You. This week, one scout fought and overcame his fear. He stood on the rappelling tower for two and a half hours, and never let go of his determination to win the battle against himself." I handed the award to Jeff, who stepped forward and addressed the crowd. "Would Jake please come down?" Jake walked down the isle amidst thundering applause and Jeff offered him the award and a firm handshake. Jake took the award and read where we had also written "We're proud of you, Jake" along the inside, then walked back to his seat. After the campfire, as the staff stood and sang Vespers and the crowd dispersed for their final night at camp, Jake and his scoutmaster appeared again. The scoutmaster told the staff how much he appreciated us all. He told us again how Jake had become a different person. And then he pulled out an award of his own. It was a thin slice of wood cut from pine, drilled and suspended by a plastic cord which turned it into a sort of medallion. "This is the Dedication to Scouts Award, and I'd like to give it to the COPE Staff." We all stood there, surprised, wondering who should step forward to accept it. Finally we all did, shaking hands once more and thanking them before they walked off into the darkness behind the other scouts. Jake and his patrol left in the morning and I never saw them again.

At the bottom of the tower stairs, I put the rope away in the waterproof box and look outside. The rain has begun to fall in sheets, and I see no breaks in the dark clouds. I'll be soaked through by the time I reach my tent, but the day is warm enough, and I don't mind. This is the kind of day I'll remember for a long, long time. The kind of day that makes me happy to be alive. The kind of day that makes me love working at camp and at COPE. A day like the one last week when one scout rappelled down our tower and was never the same. |

|